Africa’s education challenges: feedback on the review and discussions led by Wathi in 2016

Follow-up on the interview with Gilles Yabi, founder of Wathi

Can you tell us about the principal information and lessons gained from Wathi’s review and discussions on education?

We are not education specialists, even though Wathi is de facto involved in a form of popular education of the community. We try to create structured debates on all essential issues and education is clearly a fundamental question. When you initiate a discussion on education – specifically primary and secondary education – as we did several months ago, you have to research and select from a vast range of data and analyses on this subject, produced by academic research and specialist institutions. Contributions from stakeholders in the national education systems also give a very detailed view on real functions and real issues.

We have gained a lot of information and results from this. The first observation is that for everyone involved in the debate, education is the top priority of all priorities. It is the universal means of fighting against all types of problem: insecurity, unemployment among young people, extremism, poverty, etc. The second conclusion that can be drawn very clearly from the contributions by teachers, parents of students, and the general public, is that the education systems in West Africa are in a very bad state, with teachers getting little or no training, curricula that are unsuitable for local and regional contexts, and public systems often neglected in favour of the private sector. Repeated strikes in the sector, in many countries within the region, have catastrophic consequences for students, even graduates. Governments have not grasped the scale of the challenge that demographic growth will pose in ensuring an education of reasonable quality to an ever-increasing number of students in an environment of limited budgetary resources.

Moreover, it does not appear that any review or analysis has been undertaken that has been free of any taboos and external influence, on the type of education system to be set up to face economic and social challenges as well as those relating to local and national cultures, at the same time as adapting to the global context. What are the skills necessary for the economic model selected by the country? What education system is likely to respond to this need for skills? How can the objective of constructing a national identity and regional solidarity based on shared values be integrated in the education system? Should we keep children in the system for as long as possible or diversify the state education offering and give more priority to the reality of transmission of knowledge, expertise and wellbeing to children up to the age of 14 or 15 than to achieving a target ratio of children who have passed their Baccalaureate? The debate shows that there is no easy solution, but that we have to make consistent, realistic and considered choices.

What are the challenges around education in Africa today?

We have to rebuild the education systems as they were very much weakened (and sometimes broken) during the 1980s, when the African governments, with huge amounts of debt, were forced by international financial backers to make brutal cutbacks and restructure their public expenditure. Years of structural adjustment and macroeconomic stabilisation resulted in much healthier public finances but at a tremendous cost for all public policies.

In many countries, recruitment of teachers was frozen, teacher training colleges were completely closed for years, remuneration and work-life balance conditions for teachers declined sharply, and those parents that could turned towards the new private schools. This put a complete halt to the construction of public education systems.

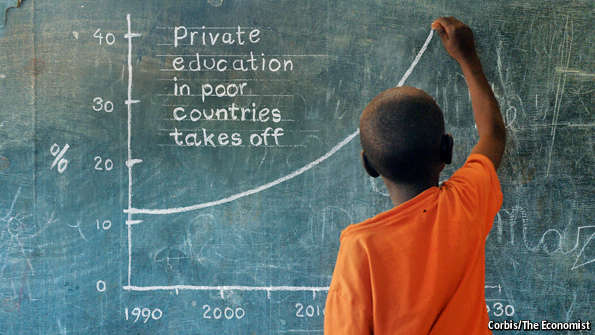

The private education offering developed at a rapid rate and the quality of this offering is now very mixed, with little control by the states. It is now necessary to bring some degree of consistency to education within the countries in the zone, including the public and the private sectors in the scope of analysis; we have to consider the training, monitoring and remuneration of the teachers, the review and revision of content, and the ending of the repeated strikes in the sector, as absolute priorities.

(You can download the Mataki documents and the WATHI5 note here, along with all the analyses and recommendations)

What do you think about the development of the private education sector in Africa?

The last twenty years have seen rapid development in the private education sector in the region, with very mixed quality in terms of the offerings. This system plays an important part, as it fulfils a need that the public system cannot, but it must be integrated in the entire system at country level. Education ministers must have a view of the whole education offering, so that approvals are not given out to all and sundry, with little control.

They must be able to verify compliance with commitments in terms of the quality of the teachers and the programmes. There must also be consistency in terms of the core values promoted via the education system. It is primarily and above all the education system that will enable us to build a peaceful and progressive society. The cornerstones of our national values must be the same for everyone and must correspond to the political choices made over the long term.

This is also why one of the recommendations from the summary of the debate is that we must have high-level, national education authorities, which must be separate and independent from the governments and which manage the fundamental choices affecting education systems in the long term, in order to set a course that is not changed every time there is a change in government.

In this regard, what do you think of initiatives like Enko?

Anything that contributes to meeting the huge needs of the education systems in Africa is a positive thing. The Enko project is driven by people who want to serve the general good of the continent in the area that, as a reminder, is the top priority of all priorities. I get the impression that there is a desire to be involved in proposing the beginnings of a solution, a standard foundation for teaching that will integrate specific local features and at the same time train future citizens of an interconnected and culturally very mixed world. The Enko schools reflect this concept and it is definitely an interesting one. The important thing for me is that there is ongoing discussion and dialogue, and adjustments constantly being made to ensure the consistency at country level and then also, ideally, at the level of each regional African community, of an education offering that necessarily has to be diversified.

Do you want to find out more about Enko schools? Comment on this post or write to us at [email protected]!